Detroit Innovation Insights: Methodology & Learnings

Jessica McInchak, Data Driven Detroit and Claire Nelson, UIX |

Thursday, December 18, 2014

This is Part 2 of the Detroit Innovation Insights series which reveals key insights collected by UIX and D3 through our three-year research initiative to identify and map the ecosystem of urban innovators and their projects across Detroit. Read back to Part 1 for an introduction and overview of our initiative.

In this post, we're sharing the questions driving our work, discussing the research methods we’ve used to understand, measure, and track innovation, and exploring the data that led us to five of our most important take-aways.

Methodology

Since 2011, we’ve connected and re-connected with 113 UIX-featured innovators to build a unique dataset representing

110 innovative projects to begin to answer the questions: Who are urban innovators in Detroit and how do they do their work? Are exchanges happening between innovators?

We’ve curated our research sample around our working definition of “urban innovation” as a new or different approach to address a civic problem, with a particular focus on small-scale, place-based projects with a social impact. This definition has evolved to encompass a diverse array of respondents who identify themselves as artists, neighborhood leaders, entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurs, technologists, community organizers, and more, and who work in all corners of Detroit.

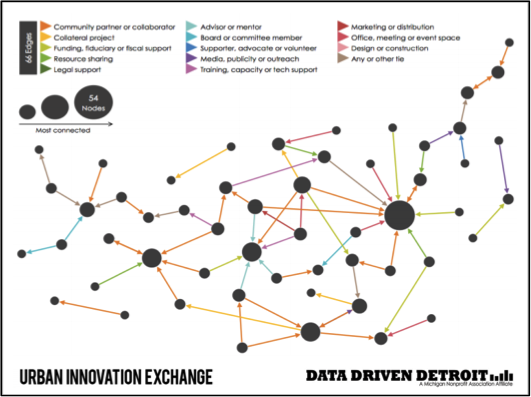

We reached innovators using two tools: a digital survey to gather demographic and perception data and a second, in-person questionnaire to map social connections, relationships, and support systems. Our digital survey data are aggregated and visualized in charts, while social connections are mapped and analyzed using network analysis techniques to illustrate exchanges happening between projects, code for unique types of support, and measure degrees of connectivity.

Behind the scenes, our network was also a tool for our research team to visually review our survey outreach and track our baseline ecosystem. Every time we mapped a new respondent and their node floated to the fringe of our map, it prompted us to ask: Where do we still have blind spots and gaps when it comes to projects happening throughout the city? And how do we reach out in more inclusive ways?

As we closed our second year, we shared Three things we’ve learned from Detroit’s innovators that encapsulated our survey data to illuminate the “who” and “how” of urban innovation in Detroit. These foundational findings were an important reflection point in our research process, but we still had questions: How is this ecosystem changing and growing? What resources and capacities are needed to support and sustain this work?

In year three, we shifted our approach to circle back to innovators and asked questions about the ebb and flow of projects over time. In March 2014, we conducted 12 semi-structured interviews with innovators who were founders or co-founders of their projects, had been doing this work for at least two years, and had participated in at least one previous survey.

We recorded hours of thoughtful conversations, coded our transcriptions for thematic patterns, and created a qualitative dataset that captured emotional testimonies and personal experiences. This dataset built on and complemented our foundation of quantitative, anonymized survey data.

Together, these data provide a picture of urban innovation in Detroit and offer important insights into innovators’ social attributes, perceptions of innovation, visions and plans, measures of success and impact, and the support systems and resources they access to start, scale, and sustain their projects.

Insights

As we close this phase of our research, we’re sharing our most important take-aways as a list of key insights into Detroit’s urban innovation ecosystem:

1) Innovators start somewhere, formal details come later.

That compelling idea scribbled on a napkin may have sparked their project some time ago, but innovators recognize that growing their project is a diligent process of refining, maturing, and often narrowing their vision. When asked how the work of the Detroit Bus Company has changed since year one,

Andy Didorosi replies, “We started this thing with really no idea how to deliver what it is we were trying to do. And I think that was a strength and a weakness. And we have maintained that sort of enthusiasm… but now with more focus. We know now what we can do and what we can’t do.”

Learning and focusing in are important for innovators but don’t always equate to being able to grow by typical metrics, like expanding products or services or implementing a 5-year business plan. Rather, some innovators like Kami Pothukuchi of SEED Wayne

Learning and focusing in are important for innovators but don’t always equate to being able to grow by typical metrics, like expanding products or services or implementing a 5-year business plan. Rather, some innovators like Kami Pothukuchi of SEED Wayne are seeking a “stability mode,” citing the importance of intentional and regular re-evaluation of their project’s purpose, in an environment that can change seemingly overnight.

Urban impact projects can take many forms alternative to typical business models. In our sample, eighty-two percent (82%) of projects are registered entities; forty percent (40%) have 501c3 or nonprofit status and fifty-six percent (56%) are licensed LLCs or corporations. (Respondents n=88). Twenty-four percent (24%) of innovators operate their project primarily from home, while forty percent (40%) have their own office, workshop or studio, or retail space. Sixty-five (65%) of project spaces are open to the public, but fewer, fifty-six percent (56%), have regular and set hours of operation. (Respondents n=75)

2) Money can’t rival their passion, but that doesn’t mean innovators don’t need it.

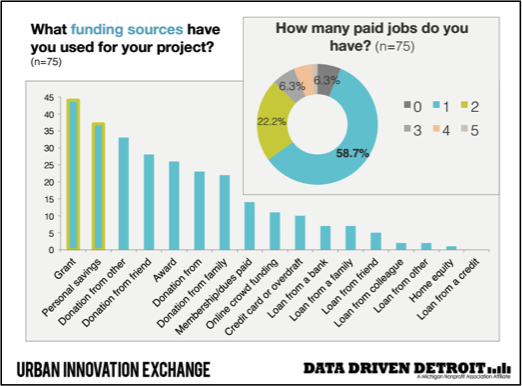

To fund their projects, fifty-seven percent (57%) of our innovators seek grants, fifty percent (50%) draw on personal savings, and many more reach out to family, friends, and colleagues for donations. It’s least common for innovators to use home equity or loans, even those from family members, to fund their work. In way of personal savings and financial resources, we’ve found that fifty-nine percent (59%) of innovators have a single paid job, thirty-four percent (34%) have two or more paid jobs, and only about half of our innovators, forty-nine percent (49%), receive income from their UIX-featured work. (Respondents n=75)

Common to our qualitative research was an open sentiment of financial insecurity; many innovators we interviewed expressed a sense of uncertainty in the future of their work, especially when envisioning five or more years into the future. Devita Davison of Detroit Kitchen Connect

Common to our qualitative research was an open sentiment of financial insecurity; many innovators we interviewed expressed a sense of uncertainty in the future of their work, especially when envisioning five or more years into the future. Devita Davison of Detroit Kitchen Connect articulates that her project, like many others, “is very vulnerable to grant funding, it is not a sustainable program on its own.”

Where do innovators need to build capacity in order to keep working towards their vision? For Noam Kimelman, when he can supplement the non-financial rewards of his work with regular financial compensation for his team, then he will be able to “really engage people in feeling ownership over

Fresh Corner Cafe.”

Audra Carson shares a similar desire to “bring people along” in this work, and until she has the financial resources that allow her to grow

De-tread’s human capital, it’s a “holding pattern.”

3) Innovators want to talk less and do more.

Attending after-hours networking events and handing out business cards at every opportunity are long gone for many innovators; these days, they’re seeking meaningful opportunities and sustained relationships that directly support their project’s operational needs and facilitate tangible exchanges, like sharing resources. As Amy Peterson of Rebel Nell notes, "You still have to hustle, you still have to make all the coffees and it’s a lot of work. But if a person can’t help you, they can connect you with someone that can.”

This finding emerged in both our qualitative and quantitative research components, drawing on interview testimonies and our network mapping of the support system innovators access. Network analysis identified that nearly half, forty-nine percent (49%) of our UIX-featured projects are connected to each other in a support system. By mapping this universe, we visualize community hubs and the actual types of exchanges happening between projects, and it’s much more than one-time conversations over coffee. Innovators are connected in a complex web of community partnerships, fiscal sponsorship, shared office space, marketing support, technical training, mentorship, and more. (Respondents n=110)

While the network is an important tool to visualize and strategically support the ecosystem of innovators, it is also a snapshot in time and we know that, by nature, urban impact projects can change rapidly. When we checked back in with Amy Kaherl of Detroit SOUP

While the network is an important tool to visualize and strategically support the ecosystem of innovators, it is also a snapshot in time and we know that, by nature, urban impact projects can change rapidly. When we checked back in with Amy Kaherl of Detroit SOUP and asked how her role and network have changed, she answered, “I stopped doing Detroit SOUP about six months ago, and I started selling SOUP. I haven’t done any work. I’ve got to sell the project, I’ve got to sell the program.” Even as a relatively established project, the theme of ‘talking versus doing’ is still apparent.

4) Innovators are vulnerable to burnout.

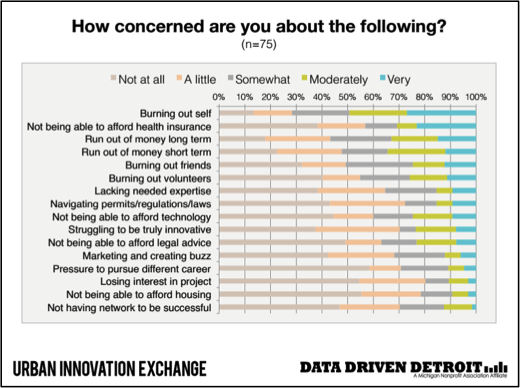

This insight may not come as much of a shock as it builds on our findings so far, but it’s no less impactful. We’ve learned that innovators maintain multiple jobs, fundraise, network, and wear multiple hats in their urban impact projects, from director to accountant to community organizer. These factors compound and emphasize what innovators are most “very concerned” about: “burning out themselves, their friends, and volunteers; not being able to afford health insurance; and running out of money in the long and short term.” They are “least concerned” about “not having the right network to be successful.” (Respondents n=75)

In interviews, we heard almost every innovator share these apparently inevitable feelings of frustration and burnout about some aspect of their work, and in the next breath speak to a deep gratitude, optimism, and inner motivation to “keep the faith.” Phil Cooley of Ponyride Detroit

In interviews, we heard almost every innovator share these apparently inevitable feelings of frustration and burnout about some aspect of their work, and in the next breath speak to a deep gratitude, optimism, and inner motivation to “keep the faith.” Phil Cooley of Ponyride Detroit explains, “It’s been a lot about trusting the vision and the process. You have to be adaptive. Because the reality is that, yes, we are failing right in the midst of the process. And if you aren’t [adaptive], if you get too stubborn on this path, it only gets worse.” For Phil, and other innovators, this ties back to the well-understood notion that doing this work requires reevaluation and flexibility because, “needs change for individuals and for communities.”

Read on to Part 3 to learn how these data insights are prompting new questions and generating recommendations for UIX Detroit and its allies to best support our community of urban innovators and their work to create more vibrant and sustainable communities.

Urban Innovation Exchange (UIX) is led by Issue Media Group with Data Driven Detroit (D3), a Michigan Nonprofit Association affiliate, The Civic Commons and a coalition of media and community partners, UIX is made possible thanks to funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

For the “Detroit Innovation Insights” presentation released in September 2014, click here for PDF.